This month dot-art speaks to artist Chris Routledge.

Chris Routledge is a photographer and writer based in the Northwest.

Chris says about his work:

‘As a visual artist, I am interested in human interaction with the spaces we inhabit. I am particularly interested in the way urban and rural landscapes contain our history. This interest in using photography to explore the landscape is informed by my academic background in literature and history, and I have been described as a documentary landscape photographer.

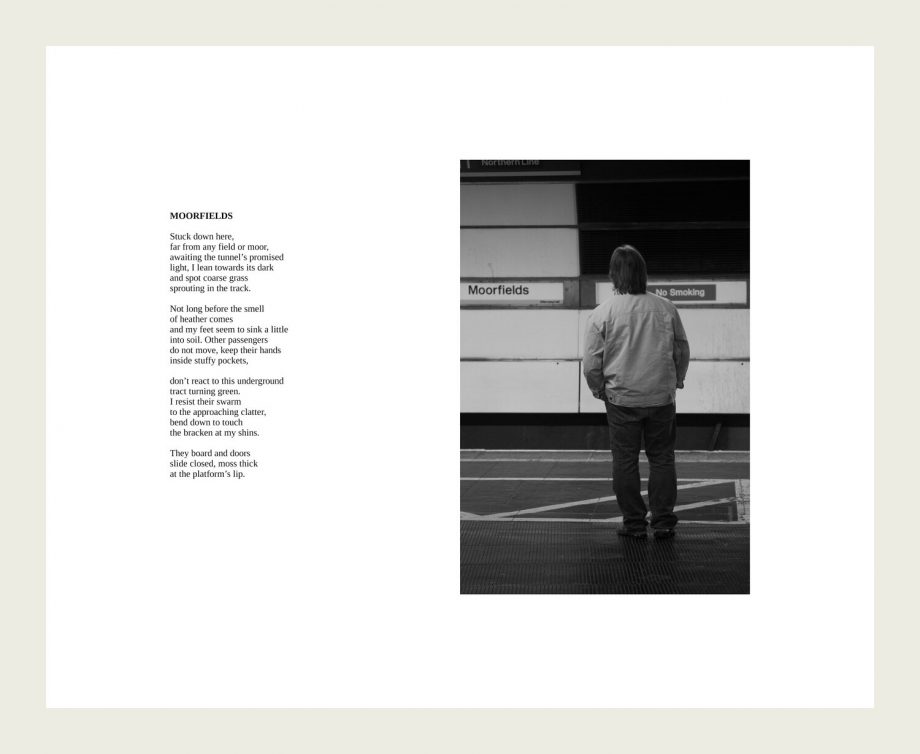

Among recent major projects is my work with poet Rebecca Goss on a collection published as *Carousel* by Guillemot Press (2018), for which I won the Michael Marks illustration prize in 2019. A solo exhibition, Indeterminate Land, documenting landscape changes brought about by Storm Desmond in 2015, appeared at the Heaton Cooper Studio Archive Gallery in Grasmere, Cumbria, in October 2019.

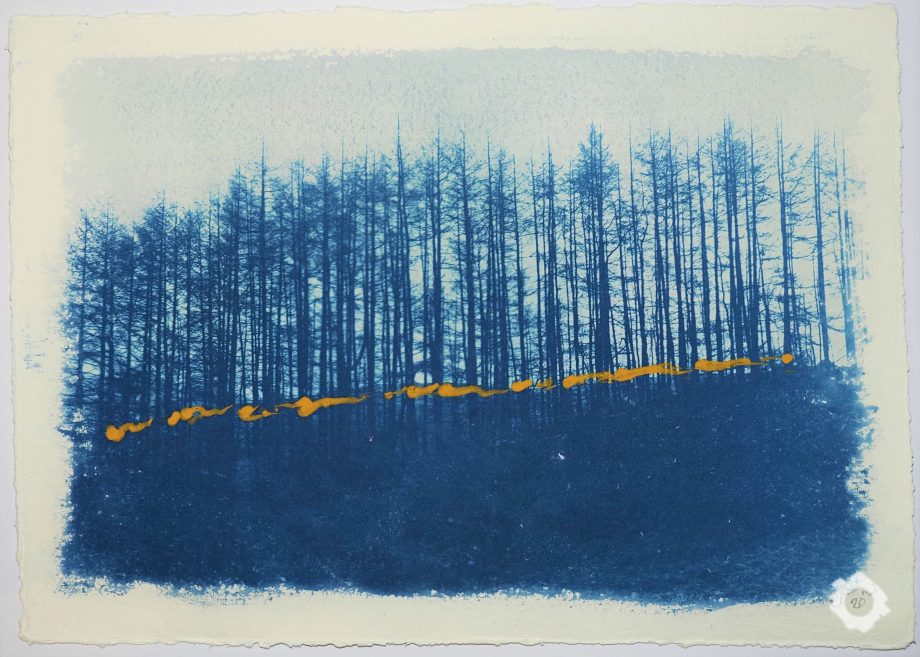

I am currently working on projects around arable farming, rural industrial landscapes, and on Rydal Mount, the poet Wordsworth’s former home in the Cumbrian village of Rydal. I work with digital and analogue media, and during 2020’s first lockdown I spent a lot of time experimenting with cyanotype printing and toning.

I have also exhibited at the Portico Library in Manchester, and at dot-art in Liverpool. My work has also appeared in magazines, including Lancashire Life, and Black and White Photography, as well as on book covers.’

Commercial clients include Rydal Mount, Zeffirelli’s 2019 Inward Eye Film Festival in Ambleside, Cumbria, National Geographic Books, and Links Project Management.

Can you describe your style of art?

My family say I make smudgy black squares, but I dispute that: sometimes they are blue, and sometimes they are rectangular, and sometimes they are even in full colour. I like to think that I am usually quite formal, from a compositional point of view, but I especially like grit and shadows. I like to make work that perhaps isn’t as it seems.

Can you talk us through your process? Do you begin with a sketch, or do you just go straight in? How long do you spend on one piece? How do you know when it is finished?

I have two ways of working.

I photograph all the time–I always have a camera with me–and so I’m constantly looking for interesting light, shapes, and unusual juxtapositions of people or things. This can throw up interesting individual photographs, but I’m also always thinking in terms of series, and that’s my second way of working: beginning with an idea and building a body of work around it. How long each piece of work takes is impossible to quantify.

Sometimes a photograph is just right there in front of you and takes about 1/125th of a second, but last week I spent seven hours outdoors, walked several miles, and exposed four sheets of film, so each of those exposures took well over an hour before we even start on developing and printing.

When did you begin your career in art?

I became properly besotted with photography around 2008, when I turned 40 and bought an old Soviet-made camera as a birthday present to myself for nine pounds. But I had my first solo exhibition (at the Heaton Cooper Archive Gallery in Grasmere) in 2019. In the same year I published an award-winning book with the poet Rebecca Goss, so if I have a career in art 2019 feels like the start of it.

Who or what inspires your art?

Mostly other artists and writers. My background is in writing and literature, but in terms of visual art I’m currently spending time with the work of photographers such as Faye Godwin, Don McCullin, and the American Robert Adams. If you want urban landscapes you can’t do better than Alexey Titarenko.

Why is art and creativity important to you?

It’s everything really. I refuse to accept that people work hard just so they can buy cars and washing machines. That would be a pretty empty sort of life.

What do you gain from being a member with dot-art?

dot-art is good in many ways. Regular opportunities to exhibit are great for discipline, and print sales are a huge privilege, but I’ve also been able to deliver workshops and photo walks. In 2023 being part of dot-art led to a solo exhibition in Hungary as part of the town of Veszprem’s European Capital of Culture year.

What does it mean to be an artist in the Liverpool City Region?

I’m a country boy by upbringing, but Liverpool is my adopted home city and I love its vibrancy and lack of pretension. It’s probably the most photogenic city in England.

What are you working on at the moment?

My big project at the moment is one I began in 2022 with a grant from Arts Council England, with the working title of Portraits from the Forest. The grant allowed me to spend some time reading and learning about trees and forests, and to change direction towards portraiture and large format photography. I’m now making work photographing people who work with trees and in conservation, and also the trees they work with. There’s a twist to how some of the prints will be made, but I’m keeping that to myself for now.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

The work you’re doing now is the work you need to do to make better work in the future. Knocked me down a peg and made me more determined at the same time.

Discover more of Chris Routledge’s work on our online shop!